Interviewed in September 2023 by Mark Laliberte

Patrick! Hi, how are you?

I’m good. How about you? I’m overwhelmed by your studio …

The studio, yeah — it’s a lot. Yours, by comparison, is very organized and tidy.

It’s just the angle.

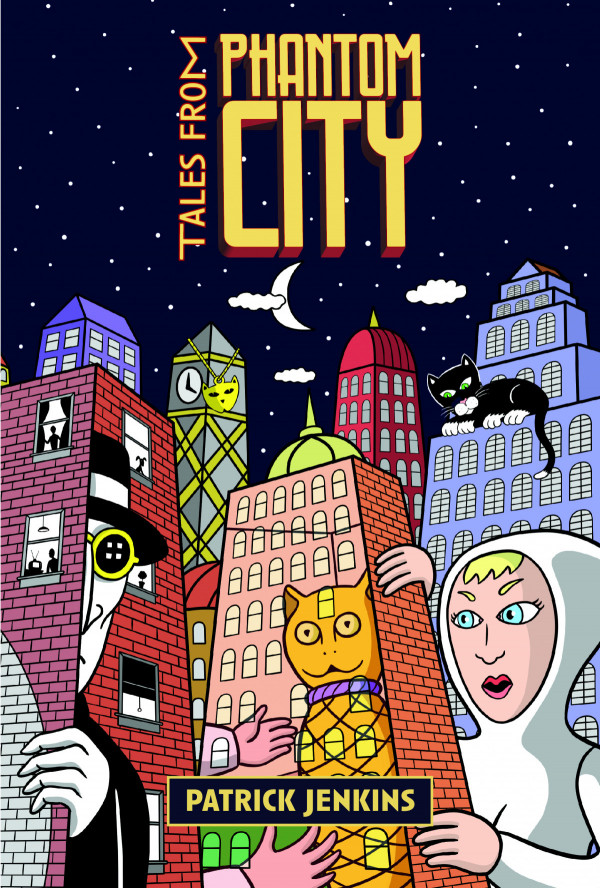

Thank you so much for agreeing to this conversation. It’s amazing to have finally seen your new book, Tales from Phantom City (At Bay Press, 2023), in the flesh; I was happy to have blurbed it … I thought it would be worthwhile for us to have a conversation that frames this new project — your first go at a graphic novel — in relation to decades of work that you’ve done in many different mediums! I first discovered your work by coming across a few of the many flipbooks you have released. You have an impressive history with creating a flipbook enterprise, and I thought maybe you could talk to us about the genesis of that project.

This goes way back … right to high school, really. When I was a teenager, I wanted to be a painter; I was also interested in film. In my hometown of Brantford, ON, we had two movie theatres, and films only came for one weekend at a time. On Friday nights, I would go see one film, usually I would see it twice — and then the next night, I would go see the other film twice. These were all Hollywood films, but there were some amazing films at that time. When I went to university, I pursued both of these interests: I was primarily doing visual arts, but I also took some film courses.

In the early ’80s, I got involved with making contemporary gallery art, and also experimental film, which I did up until about 1984. At that point, for a number of reasons we can get into it later, I felt I wanted to bring more of my visual arts training and interests into my movie making practice … animation seemed like a good fit for that.

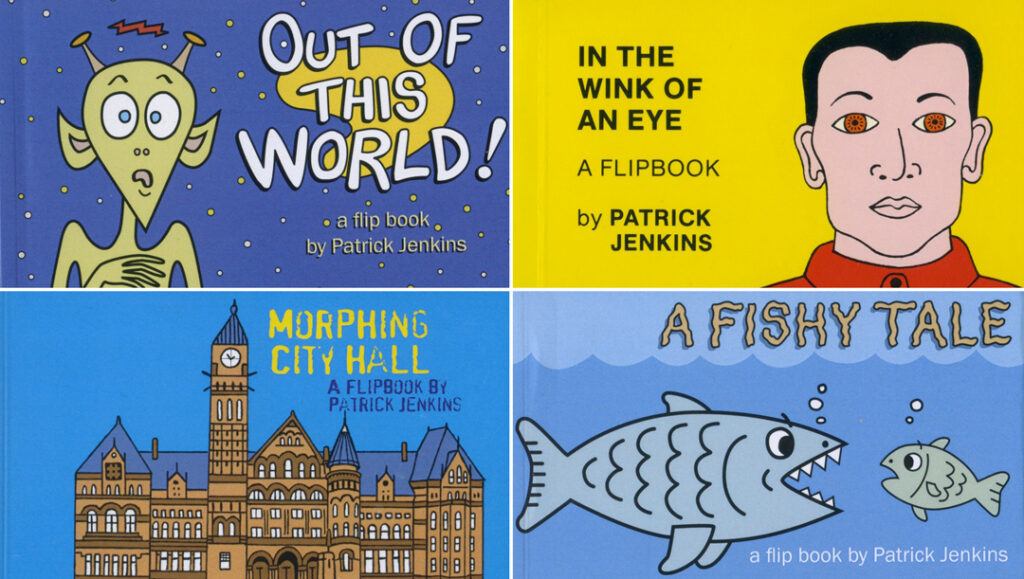

I made my first animated film, The Magician’s Hat (1986) and when I was finished I had a lot of drawings left over — hundreds of paper cels. I recalled flipbooks from my youth — I remembered really liking them, and I thought maybe I could make little books out of these little leftover drawings, just to give them another life. It was very much of the moment, I wasn’t thinking in commercial terms or anything. I got a little bit of money to print four of them — 200 copies of each — and those sold out in like a month or something. People really responded to them! So then I started to think more about creating flipbooks as flipbooks, not as an artifact from a film. The next set of flipbooks I published were designed specifically to take better advantage of the flipbook experience.

From what I could see, there were six in that commercial set. What length of time did these come out in?

There were ten, actually: A Fishy Tale (1988), In the Wink of an Eye (1987), Making Faces (1987), Morphing City Hall (2012), Out of this World! (1993), Play Ball! (1988), Skateboarding (1991), Slap Shot! (1991), The Magician’s Hat (1987) and The Magic Wand (1993). I did four books right away — and then another six books got added over the next decade. I wasn’t churning them out. They were a lot of work, each one took me about three weeks to draw, and I did it in a very low tech way: just with index filing cards and a light table, paper clips and a clamp.

It was a self-publishing venture that all of a sudden turned really successful, at least in my terms — I ended up selling 90,000 flipbooks in a decade. That was not bad, but most of the time ended up being used up on the tasks of shipping and receiving. I had to get the books shipped out to stores; everything was focused towards that. I was maintaining this little business, and selling books. It was a real hit, very energizing. I quite enjoyed doing it, and people responded to them. They wrote me letters sometimes; it was all very cool.

How were you printing the books … were you doing large runs or small batches?

The first run of four flipbooks were printed in an edition of 200 each. But it got bigger and bigger with each subsequent printing, and at one point I placed an order with a printer for 25,000 books in total! There were four titles in that order, so 5,000 were printed of three of the books and 10,000 copies were printed of a popular one called Play Ball! about baseball. I remember writing the cheque for that; I was going: I hope I know what I’m doing.

Why did you stop?

I had sold a lot of books. My major client was called the Museum Company. They were located in major malls throughout the U.S. They sold thousands and thousands of my books. It was crazy! 90,000 books sold! I had to ship all those books. After four years they weren’t selling as many as they liked, so they stopped distributing them. That’s business. At that point I thought, “You know I’ve had 10 years of this; I’m going to try something else.” It seemed like a good time to stop and explore something different.

I think that’s an important thing for a creator to make peace with. When an artist is taken by surprise by success, they are sometimes in danger of compromising out of a desire to maintain that success. If they don’t watch it, they can get stuck … you have to know when to move on, and clearly you were able to do that.

Yes, in the case of the flipbooks, they had more or less run their course as a publishing project. I’m a person with a wide range of interests — visual art, illustration, animation, moviemaking, literature, comics — so there are a lot of things that I want to explore. Sometimes these shifts in the medium I’m working in are serendipitous, opportunities that present themselves. I’ve learned to go with the flow of my interests. I think it keeps things fresh for me.

Brian Eno says that artists divide into two categories: farmers and cowboys. “The farmer is the guy who finds a piece of territory, stakes it up, digs it, cultivates it, grows the land. The cowboy is the one who goes out and finds new territories.” So you either dedicate yourself to obsessively revisiting a single idea from many angles; or, you continually look to the horizon, thrive on the act of discovery. I sense that latter tendency in your career.

Hmm, I think for me new mediums are always exciting. At art school, we were taught that an artist could work in any medium. So I had no problem with shifting and exploring new areas. I started with exploring and exhibiting drawing and experimental films. Then I felt limited by that and looked for new areas to explore like animation, documentary filmmaking and graphic novels. However, I don’t just flit from one thing to another, often I explore an area for 10 to 20 years. Once I hone in on something I want to explore, I do a body of work there; so in that sense I can relate to the analogy of both the farmer and the cowboy.

Looking forward, I think the most significant aspect of your career has been a sustained relationship to creating animated shorts. Can you give us a bit of background about your approach to animation?

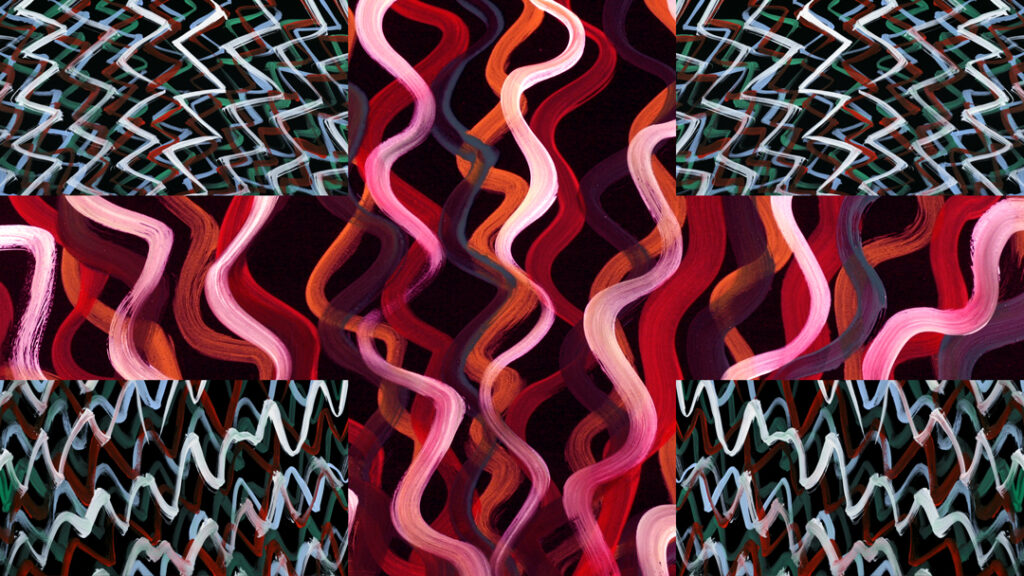

It evolved over time. Initially I was drawing on paper or using cut-out puppets to create animation. Then, around the early 2000s, I got interested in paint-on-glass animation, which is basically a form of stop motion animation where you take a photograph of a wet painting, and then alter the painting a tiny bit, adding and subtracting paint, then take another photograph, on and on, to create the animated movements. The result is that the paintings look like they are coming alive.

Simultaneously, I started to think about narrative, film noir and surrealism. I started thinking about telling a film noir detective story, into which surreal images from the afterlife or other worlds could intrude. This was a very exciting idea to me, as I’ve always loved storytelling, especially stories with extraordinary things happening in them.

Is your studio at your home these days?

Yes. I was really energized when tools like digital video, animation and editing on home computers became available. There are real advantages to digital. When shooting digitally, you can see the work that you’ve created right away. That impacts your ability to be freeform in a good way. I like working at home.

Are you working in your studio every day?

I try to; but life keeps interrupting all the time. In reality, it might be a year’s work in the studio completed over two years time, because there will be some gaps. I’ve got to make money, that kind of stuff. But I try. If I get a shot a day done — not a scene, a shot — that’s good. And if I get two shots, that’s an amazing day. But it’s usually just one.

Let’s define a shot, and explain your working process.

A shot is the basic unit of filmmaking. It could be as simple as a close-up of somebody blinking. A number of shots make up a scene in a movie. Sometimes all you get done is one shot in a day of animation. It depends on how complicated the scene is, how many characters are moving, how much action occurs and how long that goes on. Ideally, I will try to get a shot done in a single day, but some shots might go on for three or four days; it depends how complicated the movement is. It can be physically draining, very stressful. There are days when I have to push myself, because it’s not necessarily a pleasant experience — but with animation you have to focus on the bigger goal of completing the film. A lot of days, after animating through a four-hour session, I would think, This is crazy. What am I doing? And then I would play it back, and think, Okay, let’s do another shot tomorrow. Animation can be addictive that way. You swear you’ll never do this again, but the thrill of seeing the images come to life is so exhilarating, that you want to do more.

From the visual side of things, is this always solo work? I know your credits list sound people, composers, things like that.

Oh, yeah, absolutely. In terms of animation, it’s just me; I do everything. The same composer, Paul Intson, created most of the soundtracks for my films. They are all scored after the fact. We discuss the film and what music would be appropriate. He goes off and creates temp tracks, improvising a response to the film musically. Sometimes his music is quite different from what I thought they would be. We discuss it again and he refines it from there. I really like the musical scores he’s created for my film.

I thought we could talk about a few of your short films now … can we start with Labyrinth?

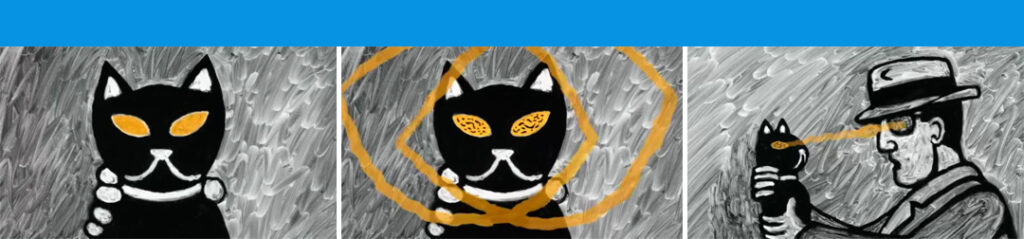

Labyrinth (2008) is a surrealistic film noir, a story about a detective who encounters beings from the afterlife while experiencing strange phenomena. It was my first film done using the paint-on-glass animation technique. I wanted to use the film noir genre, as it’s something that audiences are familiar with, but I added surreal elements to it. The synopsis is: a detective is given a heart-shaped locket and a key to a hotel room by a mysterious woman who’s being chased by some shadowy figures. He goes to the hotel and is led on a strange investigation to a diner in the middle of the desert where he’s fatally wounded. He’s reunited with the woman at the end but things do not end well for him. The imagery in the film is painted with white outlines on a black background, giving the images a look like a photographic negative, where positive and negative are reversed, creating an eerie feeling to the film.

Next came Inner View (2009), a film I did as part of a commissioning series about Kazuo Nakamura, one member of the abstract painting group, the Painters Eleven. There were eleven animators involved and we each chose a member of the group and did an animated film in response to their abstract art. I chose Nakamura specifically because I love his work. He did abstract paintings and sculptures that reflected his interest in mathematics, physics and science. I animated his paintings being created stroke by stroke on the screen, as if by an unseen hand. I was honoured to do a film about his art.

After that I did an abstract animation called Amoeba (2010). I had this piece of music, ‘Shilhim’ by John Zorn (performed by his Masada group), that I really loved and wanted to animate to, and I thought, “Okay, how can I do this?” A friend of mine said, “Why don’t you just contact him?” I did, and John Zorn agreed to let me use the composition. It’s kind of a companion piece to Inner View, it reflects my love for abstract painting. The music drives everything in this kinetic paint-on-glass animated film. I created and edited the animation in response to the music. It took me a month to create; I did it really fast.

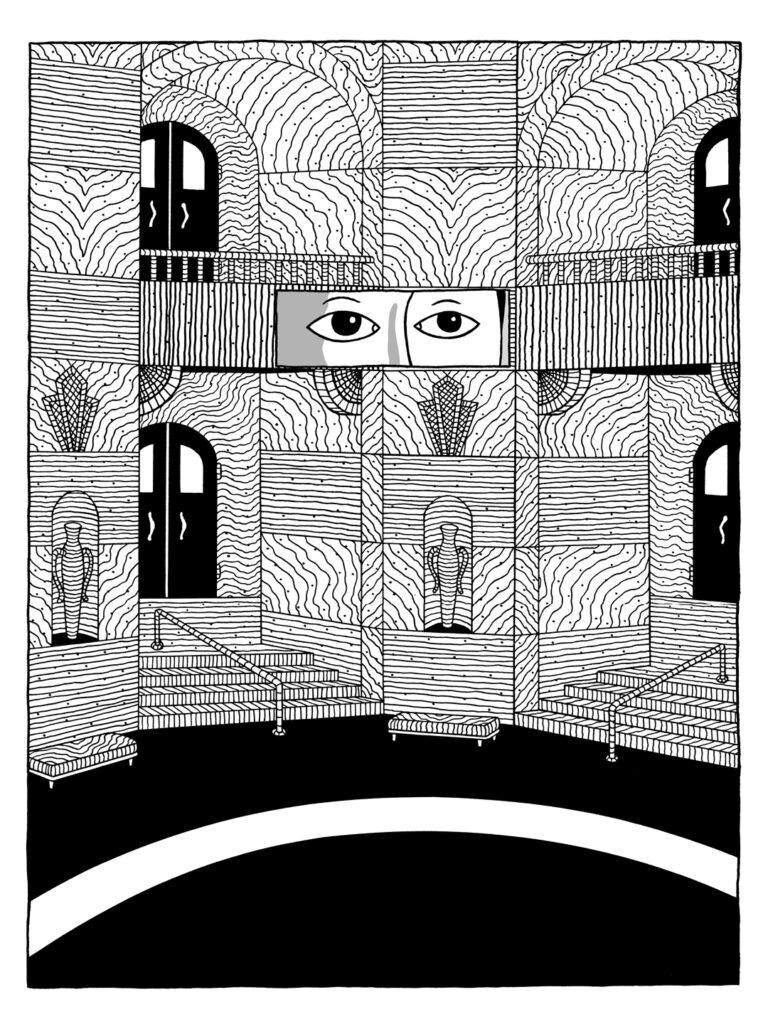

Next, I did another narrative film, Sorceress (2012) — a mythological adventure story based on Medusa. The look and feel is similar to Labyrinth, white lines on a black field with little bits of colour. In it, two sisters go on a trip to the big city to see a rock concert. Leaving the concert, one of the sisters is kidnapped by a malevolent Sorceress figure with snakes for hair. The other sister escapes into a museum where she is menaced by the Sorceress and eventually rescues her sister from its grasp.

In between I did a pair of short pieces called Towers Rising (2009) and Tara’s Dream (2010). These are short improvised animated loops. They are very gentle in nature. I wanted to do something lighter and more serene after making Labyrinth.

In Towers Rising I animated this image of three high-rise buildings flying up into the sky. Then we zoom into the window of one apartment and a woman is lifting up a bowl of soup to drink. Reflected in the surface of the soup are the three high-rise buildings flying up and the loop repeats. I realized after completing it that it was a response to the events of 9/11. Instead of towers falling, it was towers rising: an animated poem of hope.

Tara’s Dream was animated at the same time. We see the same woman floating up in the air. We see her cat sitting on the windowsill of the apartment. It jumps off the sill and she flies in through the window of her apartment and sits at a table looking into the soup bowl, and the loop starts again. It’s a gentle, meditative piece in response to a crazy, hectic world.

That brings us to the most relevant film for this conversation: Phantom City (2015). Can you briefly introduce this work?

Phantom City is the third ‘noir’ I created. This film was rendered in black and white with gray tones to give the imagery a gritty feeling. At the beginning of the movie, a hooded woman is sitting in a doorway looking at a movie theatre across the street. A detective, carrying a suitcase, stops in front of her briefly and walks on. She eventually enters the movie theatre and watches a film entitled Naked Angels; she sees the same detective, the one from outside, stealing the suitcase. He carries the suitcase to a hotel room and opens it up to reveal a cat-shaped urn. When he uncaps the urn, all hell breaks loose.

The film plays with the parallel realities of the onscreen movie and the woman watching the film. Although it has a coherent narrative, it was made in an improvisatory way: there was no storyboard or plot outline, just a set of key images. I started with the opening scenes mentioned above, discovering and animating the story as I went along. It was a risky thing to do; usually you plan everything out in animation, because it’s so much work.

Want to see the Phantom City film?

CAROUSEL has been given exclusive access to present this surreal / postmodern neo-noir, paint-on-glass animation for a period of one year … enjoy watching this amazing little short film by clicking the link below!

Watch now

This short film, which you debuted in 2015, has a strong relationship to your new graphic novel, Tales from Phantom City — with almost a decade separating the two works. How did you make that leap into comics?

My interest in comics goes back to the late ‘70s. Back then I was very excited to discover Heavy Metal and Raw. I found these magazines really inspiring and wanted to do some comics of my own, but it took me a while to get around to doing that.

I did several one-page comics in 1990 at the suggestion of Chris Oliveros, the owner of Drawn and Quarterly. He had seen my flipbooks and thought I should try comics. I did a number of them in a ‘clear line’ style and he published one in Drawn and Quarterly magazine. The others were published in Don’t Touch My Comics, an indie magazine out of Toronto. I was heavily involved in animation at that time so I didn’t pursue making comics any further until around 2013.

As much as I enjoyed making my own animated films, I was intrigued by the possibilities for storytelling that I saw in graphic novels. I wanted to get back to drawing. Around 2013, I did some test comics pages and found I really enjoyed it. In 2017, I received a Chalmers Art Fellowship (a grant from the Ontario Arts Council) that specifically allowed me to pursue a new career direction, and with that financial assistance, I created the rough outline of Tales from Phantom City. The artwork for the graphic novel took another two years to create after that.

It is interesting to compare the film to the graphic novel; I enjoyed contemplating them as parallel works. Was there something you wanted to say about the two together?

When I did my film noir movies, I was playing with the elements of noir narratives. I was also playing with magic realism, which is a South American literary movement where supernatural elements into the real world. I would take the archetypes of detective films — the downtrodden detective, the mysterious woman, the shady or potentially dangerous assignment — and play with them to create a story. However, I also wanted to bring in supernatural, surrealist or otherworldly elements into the mix. I was striving to create a new hybrid of noir and magic realism.

When I develop a story, I don’t have a plot outline or overarching message in mind. Instead, I discover the story as I write, draw, animate … it’s a voyage of discovery. When it came time to develop the graphic novel Tales from Phantom City, I took some of the motifs from the Phantom City film — the cat urn, the suitcase, the detective — and utilized them in a different combination to develop the story. Ultimately, the film and graphic novel present different stories, but are composed of similar elements. I like the idea of permutations.

How long did you work on the graphic novel?

I’ll say three years — but it was spread over eight years, as I did the test pages way back. I would work on the graphic novel between film projects. Initially, I thought it was going be a much more abstract book than it ended up being. That was part of the process: finding what I was interested in. The story evolved like the films: Here’s the blank page, here are a couple of sketches … let’s go from there.

You debuted the graphic novel at the 2023 Toronto Comic Arts Festival (TCAF). Did it live up to your expectations?

TCAF went very well. The book sold well, it was a good experience. Additionally, as part of the festival’s programming, a Toronto-based theatre company called Comic Books Live!!! did a live reading of Tales from Phantom City in front an audience in a bar in Kensington Market. Director Luis Fernandes and six actors took on the various roles, performing the dialogue and narration from the book. They performed it again in August at the Assembly Theatre.

Do you plan on doing another graphic novel?

I’m actually working on two right now: one is a sequel to Tales from Phantom City and the other is a book of short comics stories based on real incidents from my life.

Want more?

You can also watch Patrick’s latest short film, Hall of Mirrors (12m43s, 2022) for free at CBC Gem’s Canadian Reflections site, accessible to Canadians only

Watch now

Patrick Jenkins is an award-winning artist, film director and graphic novelist. His movies have been shown around the world. His first full-length graphic novel, Tales from Phantom City, was released in 2023 by At Bay Press. More on: Vimeo + patrickjenkinsanimation.com