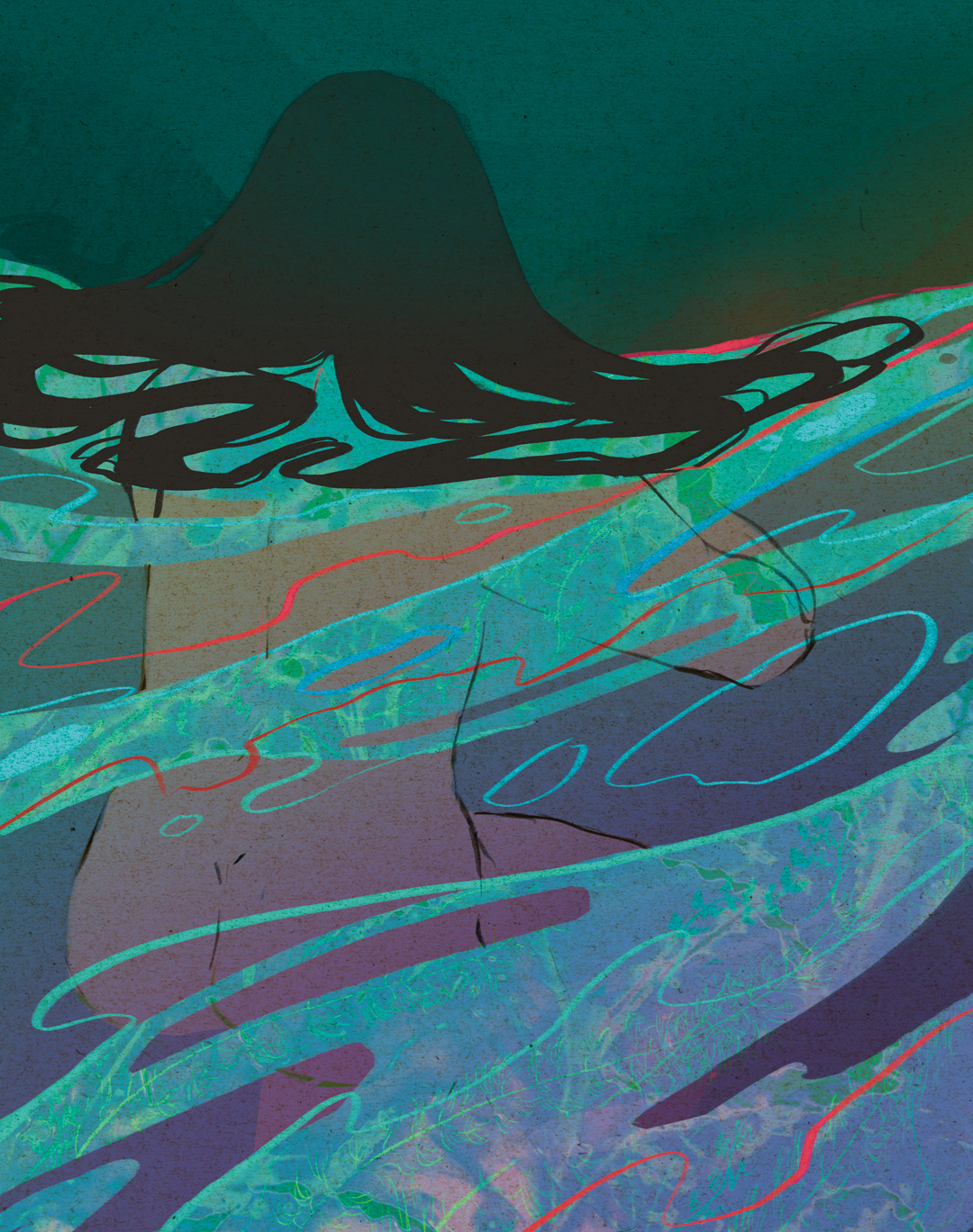

The Lakeweed Girl

The lake wanted her back. She knew it, and now her mother knew it too. Mary told her mother in the darkness of the truck’s cab as they rumbled to a stop on the gravel. The pine that blocked them from pulling closer to the shore looked neon in the headlights. The world seemed grainy and overexposed. Her mother didn’t respond right away, but she pulled the keys from the ignition so that the news broadcast halted — a drug bust in The Mission, a man’s body found in the creek, road closure on 97 after a head-on collision — and after a moment the lights went out in the cab too. She felt her mother reach across the console, searching for a hand, and Mary waited until her mother was retreating before reaching out to touch her fingers. She felt her mother relax behind the wheel.

“You know,” her mother answered, “if that were true you wouldn’t have been given to me in the first place.”

Mary felt like she should argue, but she didn’t. Her mother continued. “That’s just not the way things work. You’re not finished yet, and things just don’t work like that. They don’t.”

Mary nodded in the darkness, and so did her mother. Mary nodded because she never knew how things worked. She didn’t know when finished would be. She wondered if this was something other teenagers learned in school.

“Now you stop these thoughts because they’re not going to do you any good.” Her mother unbuckled her seat belt and grabbed the blanket from behind her seat. Mary knew she’d have to get back into the lake tonight. And she’d have to climb back out of it. Just like last month, and the month before that, and the month before that.

Her mother opened her creaking door and gave it the slam it needed to shut, then walked to the edge of the trees and waited without looking at her daughter. She looked at her less and less these days. Mary waited as long as possible before climbing out of the truck herself.

It was a boy this time. He looked about her age, though she sometimes found it hard to tell in the dark. When his mother — nervous and stiff at his side — held up her phone to check the time, Mary caught a better glimpse of his face in the light. He was handsome, like boys she saw in dance videos she watched on her mom’s computer when she wasn’t in the room. She tried to smile and he only stared at her with the indifference she was used to. She was plain. Her mother told her that a girl with her gift couldn’t be beautiful. Everyone looked straight through her, and sometimes she’d place a hand on her stomach, her thigh, her cheek, to check she was still there.

The boy shrugged out of his clothes without looking at her and stood shivering on the shore. She felt sorry for him, having to suffer this humiliation. She felt wrong for looking at his naked body, so pale in the moonlight, and she knew he didn’t want her looking, so she forced herself to look out at the lake while he waded into it, his body seizing from the cold. His shoulder blades stood out quite a lot. His arms were skinny. She wondered what was wrong with him, to be brought there. He looked like he hadn’t been eating. There had been a girl, a few months back, that hadn’t been eating.

His family stayed onshore. The mother holding her son’s clothes tight to her chest. The grandmother rooting around in the boy’s clothes to find the woman’s hand and hold it tight even though her chin was wobbling. The father shifting from foot to foot, hands buried in a plaid jacket, shoulders up to his ears. Lake pebbles shushed beneath the boy’s hikers. He didn’t look too sick. Some of the others did — hair missing from chemo, some hardly able to walk — but Mary’s mother said that sometimes it was all in the head and that sometimes the mind needed healing too, and Mary knew it. She knew it because sometimes she thought hers did as well. But the lake never worked on her the same way. She was beginning to think the lake meant to do her harm until she returned to it.

“Mary.”

She turned to find everyone on the shore staring at her. Through her, rather, to the lake. Her mother lifted a hand and Mary thought for a moment she was going to touch her, to affirm she was really there — hand to shoulder, hand to arm, hand to cheek — but instead her mother made a flicking motion as if brushing crumbs off a table. “Get in.”

Mary slipped from her baggy clothes and left them in a messy pile at her feet.

Her mother used to walk into the lake with her. She used to take Mary’s hand and guide her into the water, even on the coldest of nights, when they had to hack the ice away with an axe and a gas-powered chainsaw to clear enough room. Afterwards, at home, they would sit in front of the fireplace and her mother would hold her close and rub her shoulders and tell her how warm the water had been when she’d pulled Mary from underneath the yacht club’s wharf. How she’d heard the mewling and jumped straight into the water in her summer dress, weighed down by her shoes. How the ducks had been angry and disturbed when she’d pulled the small baby from their nests and pulled the dried, sandy lake weed away from the baby’s tiny limbs. “You were a strange-looking thing,” she always ended with, “but I knew you belonged to me.” It had been a long time since they’d sat in front of the fireplace. It had been even longer since Mary’d been told that story.

The rocks beneath her feet were slippery. Sharp in the arches of her feet. The boy’s pale flesh looked green below the surface. She was already going numb, and the boy was shivering in front of her, his teeth rattling together, though he tried to hold his jaw firm as if challenging her. She avoided his gaze, and moved behind him, as it was easier that way, and more decent, her mother said. She whispered a countdown from five, and she wasn’t sure he heard her until he took a sudden, deep breath in and held very still. She wrapped her arms tight around the boy’s middle, locked his arms to his side, and pulled him backwards into the water.

He struggled against her — they always did — as his last bit of oxygen left him. She weighed more than the boy. She held him tight as she could, even though his struggling pushed them deeper into the water. She could feel her shoulder blades press against the rocks and the lakeweed growing like moss along the bottom, as if someone was cradling her head. Her mouth filled with the hair at the back of his head. It was slimy against her tongue, tickled the roof of her mouth, blocked her nose. She held her arms so tight around him her own nails bit into her wrists. One, two, three seconds after he stopped struggling, she let him go.

The worst part was always shooting to the surface. Lake water spewing from her mouth, her ears, her pores. The weight of his body left her as he awoke, gulping in the night air, flailing his arms, trying to put distance between them. His foot clipped her knee, her shin. A heel to the stomach. She gasped and the rock she’d been fighting for purchase on tipped beneath her, and she slipped deeper, colder. Lakeweed wound ‘round her ankles. The world was dropping off.

She gave a few hard kicks — her foot finding bottom, her toes scraping against rock — and she moved towards shore, shaky and clumsy, disappointed by how easily she ripped free of the lakeweed’s hold. She was waist-deep, then knee-deep, then ankle-deep and crying, but her mother couldn’t tell as she stepped forward with a blanket.

The first time had been an accident. She was too young to have clear memories of it. She remembers rolling off a bright pink air mattress into the lake. Another child, a boy with dark eyes hovering over her on a pool noodle. They said she’d latched onto the boy so hard she’d ripped his back up. She remembers everyone staring in horror as the boy was pulled, screaming, from her arms. Her mother, soft then, cupping Mary’s face gently between her hands well the water continued to roll out of her.

The deep scratches had bled through the boy’s t-shirt. Then they were better the next day. The day after that they looked like rosy puckered lines of unbroken skin. So she imagines. Her mother, holding Mary’s hands tight — too tight –=— in her own, her face so close Mary could count every lovely freckle on her face. “You’re a gift, Mary. I dreamt it.” Maybe she did. All Mary ever dreams of is rocks and sunken logs. Darting silver fish. Pale, greenish limbs. Sand in her mouth. A weight, so real, like stones tied around her waist, holding her under.

The boy, this beautiful teen, had already been wrapped in a blanket, towelled off, his dark hair tousled. His grandmother was patting his bare, bony knee over and over and his mother was openly weeping, holding a wet towel to her face. They’d brought folding chairs and were arranging themselves around a metal fire pit off the beach. The father was down on his hands and knees making a tipi of sticks and newspaper, a bundle of gas station-bought logs next to him. They had a bag of marshmallows, salt and vinegar chips, a cooler and hot dog buns. The boy, teeth chattering, passed a thermos to his mother, who was laughing now.

How do they know it even worked? What does it feel like? Is it pulling free of the lake, of me, that saves you? She wanted to know.

Back in the cab of the truck, Mary’s mother turned the key in the ignition and they listened to classical music on the CBC. They would wait there until morning or until the family left. She’s not sure when waiting became part of the ritual, but when she asked, her mother just said, “They’ve trusted us, Mary, we don’t just want to run off, it’s part of the contract.”

She wanted some hot cocoa and marshmallows too, but she knew not to ask. She’d like to curl into the boy, underneath his blanket. Touch him in a way that gave her some pleasure, too. They wouldn’t want her there with them. Her mother turned the radio off as if hearing her thoughts.

She wondered what would have happened if it hadn’t worked. If he’d sunk to the bottom of the lake like the drowning victims they never found, the ones her and her mother heard about every year on the radio. Would he become something else?

She imagined the boy moving his hands over her in the water. She wondered what it would have felt like if he’d had his arms around her. What it would have felt like if he hadn’t fought against her. If he’d drowned, she could have stepped deeper into the lake. Let the weeds curl around her ankles. The mossy stones press into the soft parts of her. The lake fills every inch of her.

Her mother put the bulging envelope from the parents into her purse, then tried to find Mary’s hand in the darkness, not looking her way. But Mary moved out of reach, and after a moment her mother put her hand back on the steering wheel.

“Good job, darling.”

“I guess.” She was stiff with cold. There was water, deep deep within her ears. She was soaked through. Seeping onto the seat of the truck. Her mother forgot to put a towel down first. The blanket Mary’d been wrapped in lay in a wet heap in the truck bed. She was ten pounds heavier. When she’d climbed out of the lake nobody had looked at her. How could people look through her so easily when she felt like she was taking up so much more space?

“You did so well. Truly.”

She held very still so her mother wouldn’t see her shivering. She couldn’t see the lake through the trees, but she could hear it. The velvety shift of the waves over the pebbles. She heard it, whispering, raging through her.

Kristin Burns is an MFA graduate from UBC Okanagan. She’s lived in Slovakia and South Korea, and has travelled the world but she finds the most inspiration for her writing closer to home. She’s interested in hypnagogic blips and writing stories that wiggle around in the deepest parts of us. More: Instagram @kdburnsy.film