Acclaimed Canadian authors Jason Heroux and Jerrod Edson dive into the murky waters of speculative fiction for an illuminating conversation that bends the lens of reality and cracks open new worlds of possibilities for writers and readers.

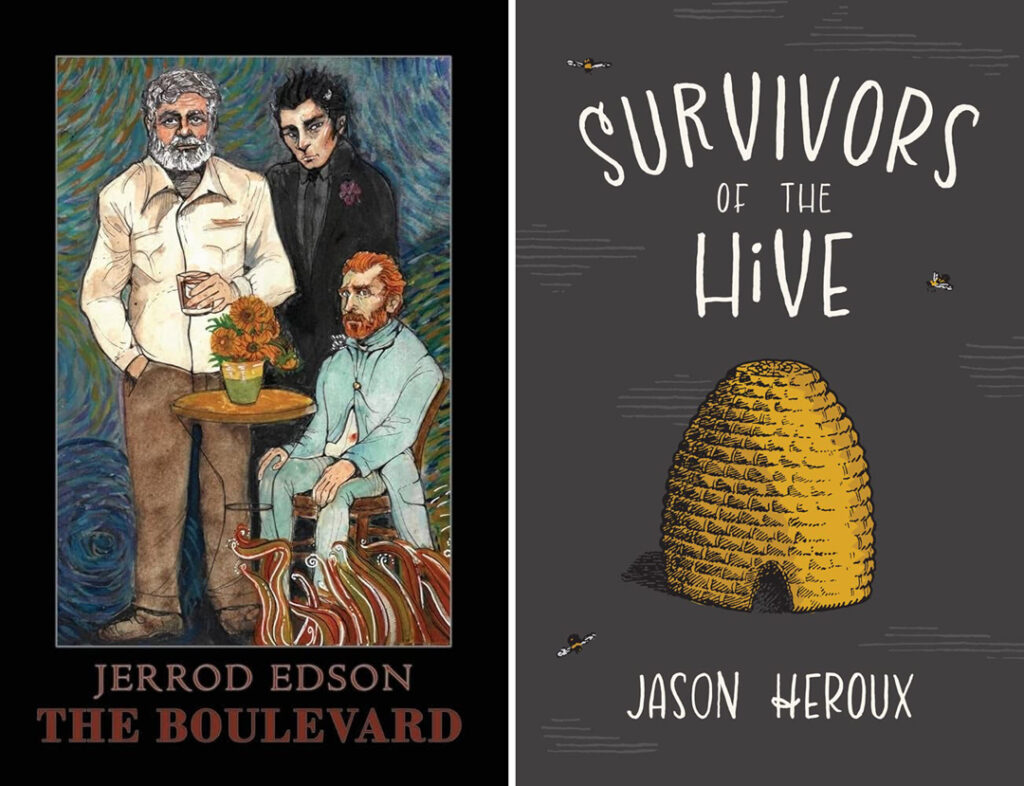

As the author of five previous novels focused on the ‘underbelly’ of the familiar city of Saint John, New Brunswick, Jerrod Edson’s latest novel,The Boulevard (Galleon Books, 2023) marks a surprising turn from realism into full-on speculative fiction. In The Boulevard, Edson snatches famous figures Vincent van Gogh and Ernest Hemingway from the annals of history and situates them alongside Satan in Hell.

Jason Heroux, by contrast, is well-versed in speculative fiction, having authored three previous novels in the genre. His newest work, Survivors of the Hive (Radiant Press, 2023) is his latest foray into alternate realities. Described by James M. Fisher as “fantastic realism,” Survivors of the Hive tells four brief tales of an apocalyptic poetry contest, desperately important centipedes, a private detective in search of lost silence and a mysterious community of naysayers.

What finally brought Jerrod Edson around to speculative fiction? What keeps Jason Heroux working in the genre? CAROUSEL is pleased to bring you this author-vs-author style interview in which the writers hash out their, and our, complicated relationships with an increasingly popular mode of writing that gleefully disregards any lines we try to draw between literary and genre fiction.

Interview conducted fall, 2023

JERROD EDSON: Jason, you’ve recently said: “Surrealism gives me the most freedom to go where I please.” Is there a limit to where writers can go? How do you keep the reader along for the ride?

JASON HEROUX: I don’t think there is a limit to where we can go. There’s certainly less of a map with speculative fiction, which means more room for error, more chances of getting lost …

JERROD EDSON: Being new to speculative fiction, I found it almost more difficult to write. Testing the boundaries of where I think I can take a reader — understanding that there still needs to be believability — is a challenge.

JASON HEROUX: I’m not overly concerned with believability; so many unbelievable things happen to people everyday. I think it comes down to finding the right balance in the writing. If I sense a scene is becoming too far-fetched, I’ll introduce more ordinary elements to even things out. It’s almost like cooking a meal: if a dish is too sweet, there’s no point trying to remove the sugar so you add a squeeze of lemon.

JERROD EDSON: I really enjoy this balance in your writing; there doesn’t seem to be any overt attempt to journey into the ‘weird’ — it happens organically. In your eyes, is the ‘weird’ of the world always present, just kind of waiting to be found? It reminds me of the way you describe poetry in the short story ‘The Last Poetry Contest’ (which appears in Survivors of the Hive): The poems write themselves … and the poet is merely the channel, the conveyance …

JASON HEROUX: Yes, I sense the ‘weird’ of the world is always present, waiting to be found. It’s not even weird on its own though: we make it weird. If something is beyond our comprehension it seems weird and makes us uncomfortable, and I’m not sure why people feel that way. Why not sit with our bewilderment and learn from it?

Poetry is a good example, because poems, like life, are full of ambiguity — and readers can feel challenged by the uneasiness of that. It’s the same with speculative fiction. There are other genres that are more utilitarian, designed to be useful or practical, and weirdness gets in the way of that experience. I guess there’s a reason why we don’t see many speculative memoirs or cookbooks … 100 Impossible Meals to Make in Your Dreams. (I’d love to read that!)

JERROD EDSON: In your everyday, does the ‘weird’ show itself more clearly to you than others, or is it something you’re more keenly looking for only when working on something new? How does this affect your process?

JASON HEROUX: I don’t think the ‘weird’ shows itself more clearly to me, and I’m not necessarily looking for it when working on something new. I find it’s simply part of an authentic human experience. Do we lead ‘realistic’ lives, or ‘speculative’ lives? Both, really. You can’t separate one from the other. I believe the ‘weird’ has a place at the table, and a voice that deserves to be heard, and I try to honour its presence in my writing.

JERROD EDSON: You say when you start a new work “things usually take a surreal turn” … are you looking for that when you begin or does it just find you?

JASON HEROUX: When I begin a project I don’t search for those surreal turns, but it’s generally where my imagination drifts. I love to ask “what if … ” and then wait for the surprise to find me. I think that’s all it is … approaching the page with questions, instead of answers. In those moments when surprise doesn’t find me, it usually means I’m not asking enough questions.

JERROD EDSON: When I picked up Survivors of the Hive at Indigo, it was in the Fiction / Literature section, it wasn’t in Science Fiction / Fantasy. The book is labelled by your publisher as a work of speculative fiction, but the thing is, there’s no section for that. Why the grey area for spec fic?

JASON HEROUX: I’m not sure why there’s no section for speculative fiction. I think it might have something to do with spec fic being a super-broad category for books that aren’t quite in the ‘tradition’ of sci-fi or fantasy — speculative fiction encompasses such a wide spectrum, you never know what you’re going to get. It’s all about the unmapped, the strange, the mysterious. I love that about it. But that can bring marketing challenges: How do you promote the unfamiliar? How do you put a label on the unknown?

Which brings me to a question about your novel, The Boulevard: I mentioned earlier that people generally lead both ‘realistic’ and ‘speculative’ lives, but what was it like to write speculatively about a real person like Ernest Hemingway? How much research was involved? You obviously had no template for the relationship between Satan and Hemingway so how did you navigate through those speculative waters?

JERROD EDSON: The Hemingway-Satan scenes in The Boulevard were so much fun to write. There was very little research for Hemingway; maybe I confirmed a date or two, but that’s about it. Some of his stories were made up from real experiences … I’m a Hemingway nerd. The thing was, I had to decide which Hemingway to write. In the novel, he’s used to lighten things up and so I went for the caricature: the drunken egomaniac. His language is very informal (“ain’t,” “gonna,” etc). I wrote Satan as the opposite to Hemingway: he is calm and well-groomed. Once these two personas were established in my mind, they wrote themselves. Satan has his story to tell, while Hemingway continually interrupts, injecting himself into the narrative. His ego can’t help it.

Hell was just another place to me; I tried not to look at things through a speculative lens. What mattered most was establishing the look and feel of the place, then sustaining it — like any setting. In that way, it kept me from trying to explain things too much (reminding me how far out of my element I was, because spec fic was all so new to me) and kept me focused on the story. I didn’t know any other way to do it.

Back to a story in your book, ‘The Last Poetry Contest’: Did you know where this story was going, or did you follow your main character, Carlos, along for most of the ride?

JASON HEROUX: I definitely followed my character along for the ride. I knew the narrator Carlos was going to get tangled up in a strange poetry contest, but I didn’t have a plan for what would happen next. Around the middle of the narrative, when he finally attends the poetry contest reading event, I had an epiphany that there was some corruption involved, that the contest was rigged … the character and I discovered this simultaneously. At that point, I explored what the corruption might be about, and it gradually led into the nightmarish conclusion.

I think part of my appreciation for speculative fiction, both reading and writing it, is that element of being caught by surprise. Did you experience anything similar writing The Boulevard? Were there any scenes or plot twists that surprised you as they happened?

JERROD EDSON: When I’m in the middle of a novel, I’m always thinking about what makes sense. I see it as throwing marbles in the air and making sure I catch them all by the time I’m done. My publisher says I’m a realist, and he’s right. That’s why I feel so out of place with speculative fiction.

I followed my characters in all of my previous books, always starting with a scene and seeing where it took me. But The Boulevard was planned out; I thought about it for more than a decade before I sat down to write it. It took years to map it all out so that it made sense. There were so many pieces in the air. And, truthfully, even though this story takes place in Hell, I have trouble seeing it as spec fic — whatever that is. I mean, Hell, to some people, is a real place.

JASON HEROUX: Regarding “throwing marbles in the air,” I think I do the exact same thing, except I’m never quick enough to catch them. They usually end up hitting the ground, rolling away, and my writing becomes a way to document their journey. The fact that it took years to map out The Boulevard really fascinates me. I don’t tend to map or outline narratives. I see your ‘planned’ approach as gardening, where you tend and oversee a project over time, nurturing its growth, while my ‘unplanned’ approach is closer to foraging, using whatever I happen to find along the way. Your approach is more meaningful, but you’ll still find unexpected surprises here and there. My approach is more surprising, with some hidden meaning revealing itself now and then.

In many ways I consider myself a realist as well. Over a decade ago, I said this in an interview: “Some days I don’t even see myself as a surrealist, but rather a realist de-scribing a surreal world.” I still feel that way.

As we continue to explore the parameters of speculative fiction, I notice we keep referring back to realism. It might be helpful to discuss what realistic writing means to us. As a realist, how do you go about making sense of the world around you? What is realism?

JERROD EDSON: For me, realism is nothing more than a story told as truly as it can be, even if it takes place in an imaginary world. It’s all about believability; tell it like it is. If something is believable, it’s real for the reader. Why should it matter if it is based on what the world perceives as ‘reality’? Every single world a writer creates is fictional. In that sense, Indigo has it right to shelve speculative fiction titles in the general fiction section. That’s why I struggle with categorizing things.

What is realism to you?

JASON HEROUX: Even the most imaginary worlds, as you say, could be realistic as long as they’re believable. Belief is a powerful thing. I’m not sure what is and isn’t real, to be honest with you. Is a dream real? A real brain conjures images, and we may wake up in real sweat because of it, with our real heart racing. Is tomorrow real? We act as if it is, but there is no physical proof of its presence today. Believability helps us make sense of things.

Can something be unbelievable but still make sense? I don’t know. Maybe that’s leading us closer to the spec fic side of things. I guess realism is a style to me. A style that says, “you will recognize this.” The rules of physics, the laws of time and space, will be familiar to you. If a five-foot tall talking frog knocks on the door, should a character answer? I think so, and the realism then becomes how the character responds to something they’ve never seen before. They might run and hide. They might sit numb, speechless. They might invite the frog in for tea.

In a recent post about The Boulevard, author, review and CanLit community builder Hollay Ghadery mentioned the “unfazed, world-bending AUDACITY of speculative fiction.” Did you have a sense of audacity’s presence while writing your book?

JERROD EDSON: Hell, yes! That’s why it was so much fun writing it. I thought this book was bound to offend some people, but so far it hasn’t. Writing anything is an audacious act. There’s a rule I’ve followed since the beginning: when I’m writing something that makes me think, “Oh, I can’t do that” then I must do it.

JASON HEROUX: In the dedication of your book you write that you showed an early version of the manuscript to your dad before he passed away, and I think his response sums up the secret general power of speculative fiction: “It’s different.” Speculative fiction isn’t realism, science fiction or fantasy. It’s not anything we can expect, predict, or easily categorize. It’s different.